I’ve never been into sports. Just never really understood the hype and the fandom. Nevertheless, I’m usually pretty on top of who the latest championship team is because I enjoy reading bumper stickers. I know LSU won something important. Though I’ve no idea what they won—or exactly when—I know it happened because the cars on the road told me it did.

We east coast folk are notoriously myopic when it comes to geography. In all my years, I had never met anyone who went to LSU. I’m fairly confident a random poll of easterners would reveal that most couldn’t locate Louisiana on a labelled map. I just lost my train of thought writing this paragraph because I couldn’t figure out how to spell Louisiana. But all of a sudden everybody was a huge LSU fan. So the school clearly had won something; folks were hopping on board the victory bandwagon and somewhere a Pelican State (had to Google that nickname) hipster was reminding people he supported LSU before it was cool.

This is what we humans do. Social creatures—biologically, anthropologically, theologically—we want to be part of something; we don’t want to be seen as the only one not on board with the latest big thing. So every Baltimore boy becomes an overnight “LSU” fanatic; every Nebraska native navigates a sudden “Salt Life”; every lackadaisical loafer lunges to the end of a “26.2” mile race. It doesn’t matter whether or not I know what a bayou is, whether or not I’ve ever so much as seen the ocean, whether or not I can walk more than a mile without being crippled by a stitch in my side; what matters is that I’m perceived to have done those things, that I’m on record as being part of the club. Usually, this is a fairly innocuous human tendency. But what happens when being seen to believe in something—as opposed to genuinely believing in it—carries with it a greater moral weight, a more intense ethical gravity?

This is a poignant question to contemplate during this Black History Month, as we approach the one-year anniversary of the tumultuous Summer of 2020 and its protests in support of the—apparently controversial—idea that Black Lives Matter. Do we really believe that? Or did we just not want to get left behind on last summer’s hottest trend? Has the Black Lives Matter movement catalyzed a change within us? Or did we just not want to be the only one without a black square on our Insta?

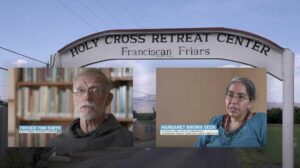

The Franciscan Voice for Justice page this month highlights several reflections, which were the fruit of last summer’s moment of cultural introspection in America. The leaders of the Franciscan provinces in the United States issued a Joint Statement regarding the protest movement, while several friars from the DC area shared their thoughts on being a small part of it.

Friar Rick Riccioli sat down with Fr. Alonzo Cox and Fr. Daniel Kingsley to discuss how to address the problem of racism in the Church.

Friar Noel Danielewicz stresses the importance of preaching truth, while Friar Franck Lino Sokpolie speaks on establishing cultures of union. Finally, Friar Douglas McMillan shares the stories of five hidden figures from Black Catholic history. Collectively, these contributions offer a Franciscan perspective on the Black Lives Matter movement.

Franciscanism offers two core themes, which together offer a critique of the movement: metanoia and minoritas.

Metanoia (from the Greek meaning “a change of mind”) is the process of ongoing and lifelong conversion. For Francis, this implied conversion away from sin and toward the Gospel, which is by definition a movement away from division and toward the commandment to love in a self-sacrificial way. Francis, in his writings, doesn’t have much to say about issues of race or culture or language. Those aren’t the categories according to which he separates people. Instead, for Francis, the single distinguishing characteristic of people was whether or not they were “living in penance,” whether or not they were engaged in a process of conversion. Conversion demands change and growth; it demands purging ourselves of our myopic views and thereby broadening our perspective. Francis doesn’t delegate responsibility for sin to some outside agent or external force. I own my sin. My sin flows from within me. Thus, when confronted with systemic sinfulness, I must ask myself how I am participating in it. Society is a collection of individual persons, its systems a collective product of those same persons. If we want a social system to change, we have to change as individuals. We have to acknowledge our sin (which includes naming it as such) and then do penance.

Minoritas is the adjectival term Francis chose as the descriptor for his brotherhood (and is the same root for our term “minority”). They were to be the Fratres Minores, the “Lesser Brothers.” Important here is that the term was intended to describe who the brothers are, and not the work they do. Francis wasn’t all that interested in “helping” the poor; he wanted to become one of them. He wouldn’t be interested in “supporting” minority populations; he’d want to identify with them. Francis understood the “LSU Effect” well ahead of his time. Supporting something, in contemporary American culture, more often than not becomes a consumeristic activity. I offer my support to a cause by displaying its branded product, to demonstrate I’m both woke and a recent contributor to the GDP. If I’m going to offer my support, there’d better be a t-shirt (or yard sign) involved! Franciscan minoritas suggests an alternative approach: I offer my support to a cause by joining that cause. I help the oppressed by becoming one of them.

Have we, over these last eight months, changed in a way that manifests we genuinely believe black lives matter? Or do we just like the cool bumper sticker?

friar Nick Romeo OFM Conv.