Panel I: Wounded Men Make the Best Friars

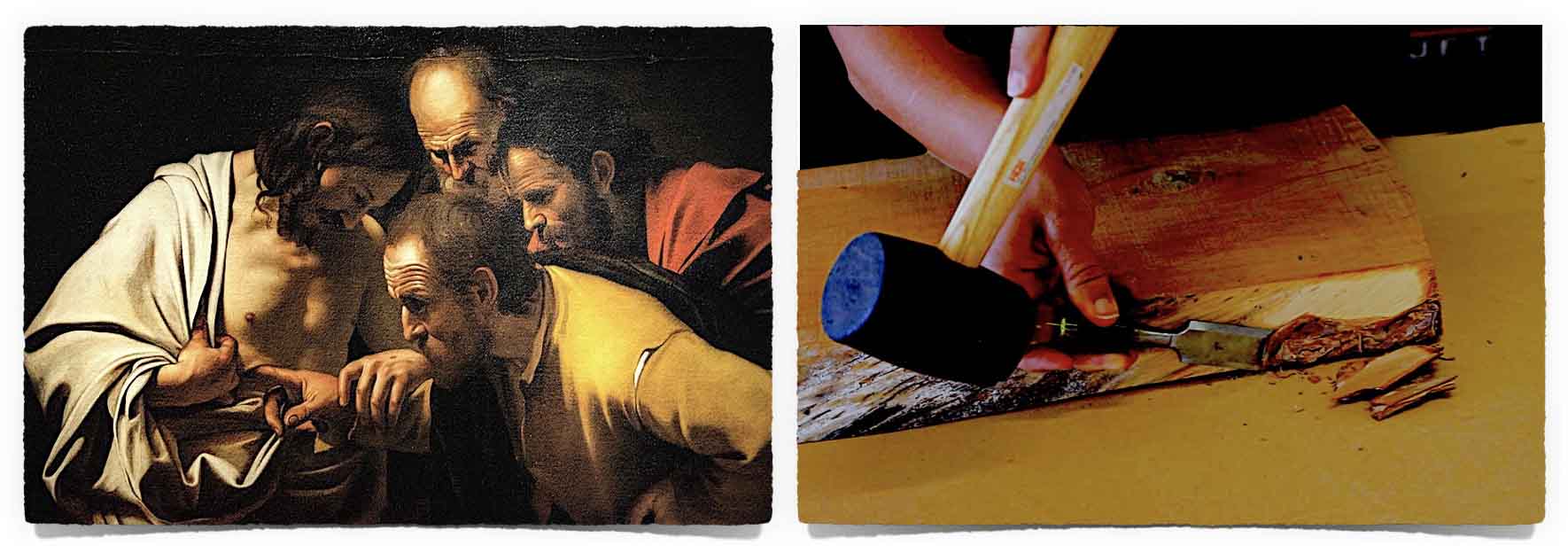

My freshmen used to revel in peppering me with religious “what if…” questions. Centuries before them, medieval theologians reveled in peppering one another with hypothetical theological conundrums. How many angels can dance on the head of a pin? is a classic. If Adam and Eve hadn’t sinned, would the Incarnation still have happened? is another. My favorite such question to pose to my students was: If the Resurrected body of Jesus is a glorified body, why does it still have the wounds of the crucifixion? How can a perfect body have a hole in it big enough for Thomas to stick-in his hand?

Part of the answer is that the understanding of woundedness as incompatible with perfection is a mistaken one. Our wounds don’t detract from our wholeness; they enhance it. It’s why a kid proudly displays his scars. It’s why a teen takes the case off of his damaged iPhone, evidence of life lived full-send. It’s why a glow stick works the way it does; you have to break it for it to shine.

Our theological doctrine holds firmly to the fundamental principle that God is perfect. But no serious reader of Hebrew Scriptures could make the claim that the character of “the Lord” is free from battle scars. God shares his deep woundedness all the time. The Lord feels hurt and abandoned and mistreated and forgotten and cheated-on. In some ways, it seems getting wounded is what it takes for the Lord to be stirred to action. It’s why He calls Moses after hearing the cries of the slaves. It’s why He tells Ezekiel He’s going to save Israel, because its exile is making Him look bad. It’s why the consecrated host has to be broken before it can be shared.

Lots of guys tell me they’re interested in religious life, but don’t feel worthy of it. Perfect, squeaky-clean, unwounded dudes make terrible religious. Broken, messy, fractured guys make the best friars, because they know they’re broken and are thus better able to embrace the messiness of their brothers and the fractured lives of the people to whom they minister.

So you’re a broken, fractured, messed-up, unworthy dude? Awesome! You’re perfect!

Panel II: The Purification of Motives

here is an episode of Friends (S5E4 – “The One Where Phoebe Hates PBS”), in which Phoebe is looking for a good deed she can perform for purely selfless reasons, something good that will make her feel miserable in the doing. She settles on donating the money she had been saving for a hamster, to a telethon. Joey is answering one of the phones at the telethon, but has been placed at a station off-screen. Phoebe’s donation just happens to get called-in to Joey, gets him on camera, and causes her to joyfully exclaim, “Oh, I got Joey on TV! That makes me feel so good!”

There is very little (maybe nothing at all) we ever do for totally virtuous motives. Most definitely, no one enters into any vocation for 100% pure reasons; there are always ulterior motivations. Folks get married because it makes for easier finances or because they don’t want to upset their family or because the guy got the gal pregnant or because all the woman’s friends are getting married and she doesn’t wanna be left out. Guys become priests because it will help them move up the economic ladder or because they’re being pressured into it or because of a perceived elite status associated with being a cleric. One of the reasons I joined the friars out of high school was to get away from some dysfunctional family dynamics.

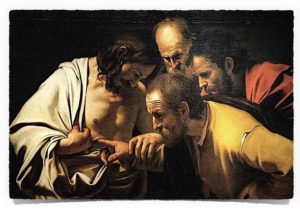

Everyone has some impure motives for entering into religious life. Part of the journey is what we call the purification of motives. Something might be a part of why you came, but it’s not going to be enough of a reason to stay. Part of the hard work of formation is owning our less-than-idyllic reasons for joining, and then permitting them to be chiseled away by the mercy offered by Christ and the humility inflicted by our brothers.

– friar Nick Romeo OFM Conv.