adapted from an article first published in San Bonaventura informa, the monthly magazine of the Pontifical Theological Faculty of St. Bonaventure (“Seraphicum”) – For full article click here

I heard a voice, rising in intensity over the hum of the market. Searching for the origin amidst the canvassed tents, I traced it to the man violently gesticulating toward his cell phone; he unleashed upon the device a cascade of expletives, the kind that caused parents to hurry along their small children. His political rant—racist and toxic—transformed the camaraderie of the bustling Arezzo market into a divisive cesspool, as onlookers took sides by a shake or nod of their heads.

This moment in the market reminded me of a story told about St. Francis’ own visit to Arezzo. Perhaps it was on a similarly crisp day, which quickly broiled into unbridled prejudice. In a painting of Francis’ visit, the primary figure is Brother Sylvester standing outside the city gate with arm raised as he casts out demons. Francis kneels close by, in prayerful support of the exorcism.

Looking back eight hundred years through the lens of this medieval painting, we understand that the real demons in Arezzo were those of social, economic, and political division. It seems these demons of division, cast out by Sylvester so long ago, have returned to settle in homes, towns, cities, and countries across the globe. They now manifest as the phantoms of political polarization.

Yes, our political life is possessed. Politics is supposed to help us collectively achieve meaningful goals not readily realized individually. To achieve this general welfare, the political process is necessarily marked by negotiation, debate, and legislation, not unlike the haggling at an antique market. But today’s political marketplace is marked by division so deep that it polarizes family members, friends, and neighbors into uncompromising camps that demonize the other in order to justify their own perspectives and prejudices.

Like the man in the market who yelled at his phone with wild gestures, the people of medieval Arezzo would have raised their hands in demeaning signs of disgust. In the painting, Brother Sylvester instead raises his hand in a gesture of preaching against the city’s divided citizens. He offers the populace the Gospel alternative of the love of God and neighbor.

At the same time, Francis falls to his knees in prayerful support of Sylvester’s exorcism. This falling to one’s knees in prayer becomes a righteous act of support through friendship. As Jesus bowed before the Father in prayer, he then knelt before the poor and those who suffered social discrimination, calling them friends.

Antique markets like the one in Arezzo can serve as a school of civil discourse. In the market’s conversations for compromise, we discover the value of the haggling itself: casting out the demons of division with an attitude of mutual respect for the common good.

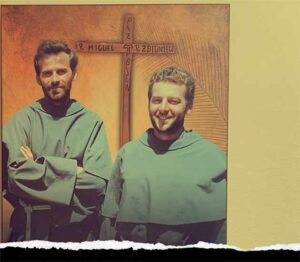

friar Michael Lasky OFM Conv.