George Harrison is my favorite Beatle. His I Me Mine is easily in my top five favorite tracks from the Fab Four. From their Let It Be album, the song is George’s lament of the selfishness and inflated egos he saw as the ultimate cause of the band’s demise. More broadly, its lyrics function as a condemnation of the obsessive individualism of Western culture, wherein self-reverence flows more freely than wine. Simple. Piercing. Effervescent. I’m jamming out to it as I write.

It’s a perennially appearing tune on the personalized playlists Apple Music creates for me. It was the song I chose as one of my “objects” for a show-and-tell assignment during a course I took in undergrad. And it was the alternative rhythm that sounded within me, while without me another hymn—part of many a friar’s vocation playlist—was being sung: John D Becker’s arrangement of the Litany of the Saints.

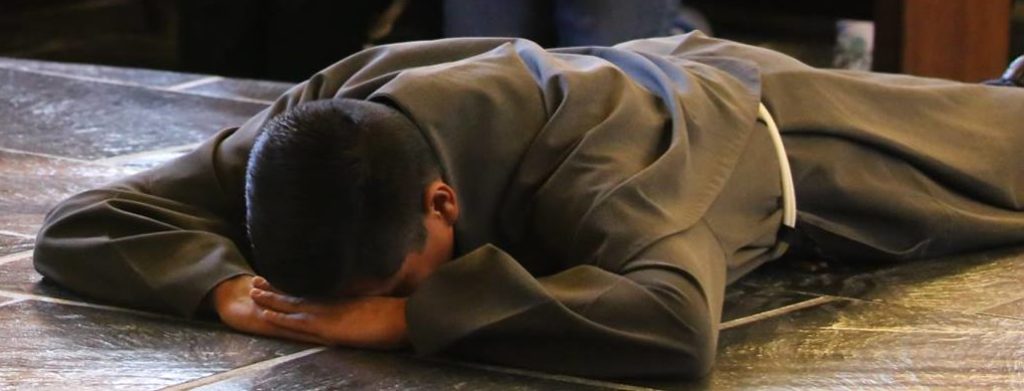

It was a bright and chipper September Saturday in Baltimore. Roughly two hundred miles to the northeast, the Occupy Wall Street protests were just beginning in Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park. Just outside, the late summer silence was harshly broken by the intermittent wailing of police sirens, the soundtrack of Charm City. Inside the limestone walls that frame the edifice of Saint Casimir Church, my chest was pressed against the maroon carpet of the center aisle, forehead nestled on the backs of interlaced hands, toes grazing the trodden pile as they slid from my Birkenstocks. I lay prostrate before the altar. Stomach doing cartwheels in my guts. Becker’s melody vibrating on the stuffy air. Harrison’s critique setting on my mind.

The prostration before the altar, most friars would attest, is the most intense moment in an already intense Rite of Religious Profession. During this poignant ritual amidst the Eucharistic liturgy in which a friar professes his solemn vows, he places his body on the ground in front of the altar; he literally embodies what he is preparing to do: consecrate himself to Christ in sacrifice and adoration, for the entire time of his life.

This richly symbolic ritual is accompanied by the congregational chanting of the Litany of Saints; as the friar offers himself before God, the whole Body of Christ—the Church in its totality, living and deceased—prays for him, that he might be able to live a life worthy of the call he has received to profess vows in religious life. It is impossible not to be overwhelmed as this tide of prayer washes over you. Equally impossible is not confronting a moment of existential dread, as you ask God what exactly He’s duped you into, whilst simultaneously recognizing your woeful inadequacy for the task. All the while you hear the voices of people, whose singing faces you cannot see, invoking the intercession of people, whose holiness you cannot grasp. You are part of a reality much bigger than yourself, surrendering to a Reality bigger still; your life is no longer You Yours, but the Lord’s. George would be pleased, if maybe a bit confused.

In a wealthy society where the multitude of options in the cereal aisle can overwhelm, zeroing in on a singular choice about anything can become a daunting challenge. In a pop culture where self-invention is serial and sacrosanct, making a final decision about anything can be a startlingly counter-cultural move. To say you are committing to something is to say you want a revolution.

A young man professing his solemn vows, making a lifelong commitment to a particular way of life and a concrete group of brothers, is a revolutionary act. It’s veritable rebellion. But it is also catalyst for hope and harbinger of a cultural and generational shift. Commitment has not, in fact, been relegated to the dust bin of history; it is not a nostalgic relic. Young people bubble with the desire to give themselves over to something greater than themselves. They languish for meaning; in the quest to discover it, they are still willing to carry the weight of steadfast commitment.

Lurking beneath the surface of the society we’ve constructed for ourselves is a deep dissatisfaction with the resulting architecture, a weariness of the helter-skelter that has resulted from the constant pressure toward status and upward mobility that accompanies the myth of progress. Downward mobility is the new flower power; a tiny house parked near a mountain lake is the new Woodstock. In this shifting milieu, the witness of the Franciscan life—downwardly mobile since 1209—is increasingly relevant and appealing. The witness of a friar’s solemn profession is that genuine peace, authentic joy, and lasting refreshment emerge, not from adhering to the caprice of the Self, but from following the commands of the Son.

“Your ‘yes’ helps me say ‘yes’.” These pithy words of friarly wisdom remind us that commitment is corporate. We need the support and encouragement of a broader community in order to follow through on the promises we’ve made; we can only get by with help from our companions. Your “I will” helps me say “I will.” And vice versa. Thus, a friar’s profession of vows is a testimony to the Church in its entirety; it points toward the value, not only of that to which a friar is committing, but of the act of commitment itself. This is why the entire Body of Christ chants together the Litany as a friar prostrates before the altar: lending the support of the we, as he surrenders all that is he, him, his to the tender sweetness of the Lord.

– friar Nick Romeo OFM Conv.